Executive summary

All-electric services deliver an apartment block’s space and water heating without using mains gas.

Each apartment is a self-contained unit, with a boiler providing hot water while space heating is delivered by a panel heater in each room. The entire system is automated, which maximises efficiency by targeting energy use as well as allowing residents to pre-set their preferred temperatures for each room.

The all-electric layout replaces the conventional service layout of piping hot water to each apartment, either from either a central plant or a district heating network. Such ‘wet’ heating systems deliver continuous space heating through radiators and underfloor units, which is necessary for many existing buildings that were not designed to prioritise heat retention.

Continuous heating is not needed in newly built or renovated apartment blocks, which are required by regulation to meet minimum standards of heat retention.

Eliminating hot water pipes substantially lowers the capital cost of an installation and removes a major contributor to summer overheating

Modern building materials retain heat so well that even during the winter, heating is only required intermittently.

Unlike radiators and underfloor units, which take time to heat up and cool down, an automated panel heater can respond quickly to temperature fluctuations and keep a room at a comfortable temperature without requiring the occupants’ attention.

Eliminating hot water pipes substantially lowers the capital cost of an installation and removes a major contributor to summer overheating, which is a regulatory requirement to mitigate (from June 2022).

In the past, there has been a tension between the lower cost-per-unit-energy delivered by gas and the need to transition to electric power, which has much lower greenhouse gas emissions.

However, another advantage of electricity is that it does not need to be imported. Replacing fossil fuels with renewables is more environmentally friendly and, in the long term, should insulate energy prices from the sort of destabilisation we have seen in 2021 and 2022.

Air-source heat pumps have been widely promoted to close the price gap between gas and electrical power, usually to replace conventional gas-powered plants at the centre of a hot water distribution network.

Heat pumps may be appropriate in an existing building that requires continuous heating but, in an apartment block with modern building materials, we have found that a wet heating system with a heat pump has a higher capital cost and at least an equivalent running cost to a self-contained service layout using panel heaters and an electric boiler in each flat.

The following article describes how and why we came to our view that self-contained, all-electric services should be the option of preference for a modern apartment block.

Electric panel heaters replace wet central heating

Electricity is the energy option with the lowest carbon intensity and as renewables replace fossil fuels in powering the national grid, that carbon intensity is projected to halve by 2035.

Electricity is the energy option with the lowest carbon intensity. Pic: Nejc Soklic

All-electric services would move the domestic sector from gas to electrical power, requiring an increase in renewable electricity generation. However, the necessary technologies are already widely used which means the components are already in mass production and there are established training programmes for the engineers who operate and maintain them.

Most building services, including ventilation, appliances and air-conditioning, are already powered by mains electricity. The major innovations required for all-electric services are in space and water heating.

All-electric space heating is usually provided by a panel heater in each room, which replaces the conventional approach of using hot water to distribute heat around an apartment block, either from a central plant within the building or a district heating network.

In recent years, air-source heat pumps have been widely promoted as a possible replacement for gas-powered plants. They work by augmenting the energy they draw from the mains with heat energy drawn from the air, reducing the cost per kWh used to heat water.

However, a system augmented by a heat pump still needs to heat and distribute a large volume of water which requires a large amount of energy, and the pipework introduces an unavoidable inefficiency because it is impossible to avoid some heat energy being lost between the plant and the apartments.

When we compared data from a post-occupancy evaluation of all-electric apartments with a model in which the same apartments used an air-source heat pump, we found all-electric was clearly the superior option.

Not only were all-electric services more efficient than the heat pump option but when we compared the results to the recommendations of the government’s Future Homes consultation, we found the all-electric apartments had been meeting the Future Homes requirements before they were even drafted.

Britain has one of the highest levels of fuel poverty in Europe despite many European countries having much harsher winters.

Building services for modern fabric standards

Many existing buildings depend on wet central heating because their fabric standards are so poor. The current building regulations mandate minimum standards for insulation and air leakage. However, most British homes have not been renovated since fabric standards came into force, leaving them dependent on wet heating.

Britain’s low fabric standards are not sustainable, partly because of the greenhouse gas emissions associated with heating poorly insulated homes, and partly because the cost is so high that Britain has one of the highest levels of fuel poverty in Europe [PDF: The Cold Man of Europe – 2015] despite many European countries having much harsher winters.

In 2019, more than 10% of British householders could not afford to heat their homes properly. Without a dramatic reappraisal of how domestic heating is provided, the dramatic gas price increases of 2021 and 2022 will ensure fuel poverty rates increase.

Improving the fabric of British homes is an important step in both decarbonising the British economy and improving quality of life.

It is part of the government’s Clean Growth Strategy and various grants are available for homeowners to improve their insulation.

With high fabric standards both incentivised and mandated, the coming years will see more homes either built with or renovated to fabric standards that make panel heaters a viable option while the advantages of wet heating systems may be outweighed by their disadvantages:

A wet heating system requires a radiator in every occupied room

Internal gains from pipework: High-quality building fabric retains heat inside a building during the winter, but that retention can make an apartment block hot enough to be uncomfortable during the summer and harmful to its occupants’ health during a heatwave.

The 2022 updates to the UK building regulations mandate mitigation of summer overheating, which is already a significant problem in British housing.

As heatwaves become more frequent, there is a risk that energy saved in lowering heating bills will be offset by retrofitted air conditioning systems.

In many apartment blocks, the problem is exacerbated by hot water pipes running through central corridors, where the lost heat cannot disperse without heating the apartments along the corridor.

Slow response times: Water’s thermal capacity makes it a good distribution medium, but it also leads to a slow response to a thermostat. As radiators and underfloor systems heat and cool, they often cause a room’s temperature to fluctuate between being uncomfortably warm and uncomfortably cold without settling at an optimal temperature.

High installation costs: A wet heating system requires a radiator or underfloor heater in every room likely to be occupied for any length of time, heavily insulated pipes to distribute the hot water and, in the case of an apartment block, fire dampers wherever pipes pass between apartments and corridors.

It is a far more complex system than having an electric heater in every room and that complexity is reflected by the cost and by higher embodied carbon.

The latter is often overlooked in schemes intended to cut greenhouse gas emissions and is exacerbated because when an existing wet heating system is switched from gas to heat pump-augmented electricity; the lower flow temperatures require the radiators and underfloor heaters to be replaced with larger units.

In an apartment block, a designer is faced with the choice of heavily insulating the pipework or a low-temperature heat network, both of which are substantially more expensive than using electric panel heaters.

All-electric hot water

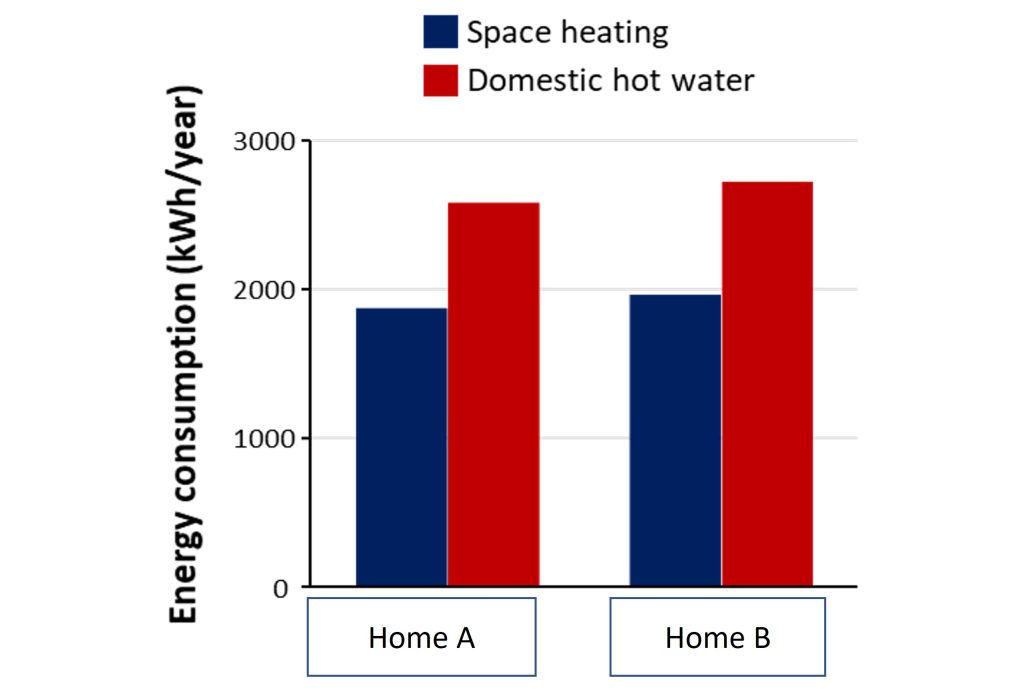

There is no escaping the fact that heating a large tank of hot water requires a lot of energy. In our post-occupancy evaluation of all-electric apartments, we found that water heating required substantially more energy than space heating (Figure 1).

Annual energy demand for space and domestic hot water derived from post-occupancy evaluation of two terrace houses in Cardiff, each rented to seven people divided between three flats. Space heating was direct electric and water was heated by direct electric power augmented by an exhaust air heat pump, all automated by atBOS

As with space heating, electric water heating needs to be compared with heat pump augmentation. Most heat pumps can only heat water to 55°C (131°F) while gas and all-electric systems heat water to 60-80°C (140-176°F). The lower storage temperature has two drawbacks:

- Because the hot water is not as hot, more of it needs to be mixed with cold water to achieve a comfortable shower temperature. In practice, that usually means converting from gas to heat pump-augmented electric water heating involves installing a larger hot water tank.

- The Health and Safety Executive recommends that stored hot water should be heated to 60°C for an hour every day [PDF: Legionnaires’ disease] to prevent it from harbouring Legionnaire’s disease which, in practice, often requires supplementary heating from an element powered by mains electricity.

The challenge of switching from gas to electric power without soaring energy bills has driven a revision of boiler design. The latest boilers use energy far more efficiently than the conventional approach of simply burning whenever the water falls below a thermostat temperature:

- EarthSaveProduct’s Ecocent uses an exhaust air heat pump to recover space heating energy from the ventilation exhaust vent. Because the exhaust air is consistently above 20°C (68°F), the heat pump operates considerably more efficiently than if it were using the usually colder outside air as a source.

- The Mixergy tank optimises energy use through stratification; only heating the top layer of water in the tank to the required temperature and using machine learning to ensure that enough water is heated to meet the needs of the occupants.

New generation boilers are designed to use electric power, either directly from the mains or augmented by a heat pump, although some are compatible with hybrid approaches that combine gas and electric power.

Heat recovery

Heating water directly from mains electricity is rarely a viable option. The energy requirement is simply too high, incurring energy costs so extreme that such a system would not pass the regulatory requirements incurred by the standard operating procedure (SAP) for calculating a dwelling’s energy consumption.

The solution is to recover some of the energy used for space heating into the hot water system. There are two ways to do that:

- Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) uses a heat exchanger in a closed ventilation system to retrieve heat energy from exhaust air and use it to supplement the space heating system.

- An exhaust-air heat pump, such as that used by the Ecocent boiler described above, similarly recovers heat energy from the ventilation exhaust but uses it to heat the apartment’s water.

Our experience is that the exhaust-air heat pump is usually the better option. An MVHR system is only cost-efficient with building materials that retain heat far more efficiently than required by regulation, and achieving those standards adds 20-25% to the construction costs required by regular standards [PDF: Passivhaus Capital Cost Research Project]

It’s a solution that has received a lot of attention because it is recommended by the Passivhaus Trust which originated in Germany where, because German winters tend to be harsher than British, the outdoor temperature is low enough for MVHR to deliver substantial savings for much more of the year.

The milder British winters rob MVHR of much of its efficiency potential, and much of the justification for its high capital cost.

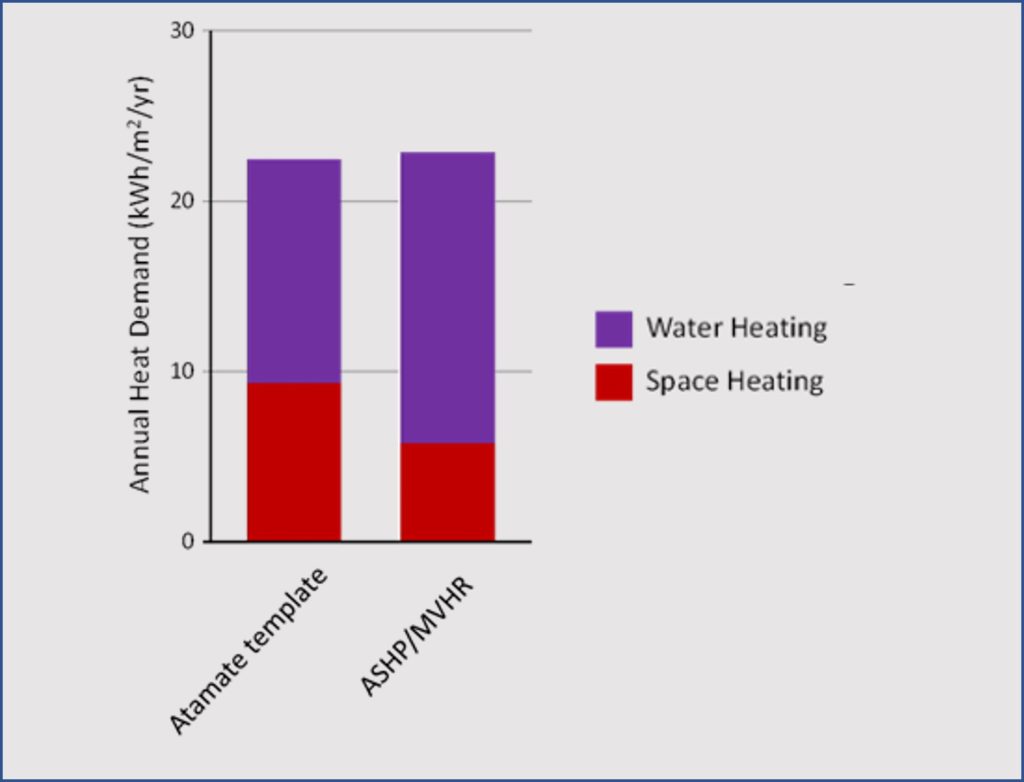

An exhaust-air heat pump delivered slightly better cost efficiency than projected for the same apartments fitted with MVHR

The fabric standards required by an exhaust-air heat pump are no higher than those required by the current building regulations and can be integrated with the ventilation system required by those standards.

It was the system installed in the apartments analysed in our post-occupancy evaluation, in which we showed it delivered slightly better cost efficiency than projected for the same apartments fitted with MVHR despite having a lower capital cost (Figure 2).

Efficiency through automation

Automation is the single most important factor in realising the potential energy efficiency of self-contained all-electric services.

It became essential when a kWh of electricity consistently cost five times more than a kWh of natural gas and while gas prices are rising, gas remains more cost-efficient in any calculation that only compares the direct cost of converting energy into heat.

Automation closes the gap by targeting heat energy to where and when it is required, avoiding the inefficiencies inherent to the intermediate step of heating and distributing water.

An operating system like Atamate’s building operating system (atBOS) constantly monitors the indoor environment and applies whatever services are required to keep it comfortable without wasting energy by using them where they are not needed. The key features for maximum efficiency are:

Zonal control applies the services to zones, usually corresponding to a single room, rather than using a single reading for air temperature or quality for the entire apartment or building.

Occupancy-based control detects which zones are occupied and keeps them comfortable without wasting energy on heating and maintaining air quality in empty rooms.

Calendar controls allow the apartment’s occupants to programme services to switch on or off at predefined times. For example, an apartment may be empty when the occupants are at work and during the winter, even a well-insulated home can become uncomfortably cold when it is not heated for several hours. The calendar function allows the occupants to over-ride the occupancy controls and switch on the heating a few minutes before they arrive home, ensuring that it is at a comfortable temperature when they do arrive.

Flexibility allows an off-the-shelf system to be tailored to whichever services can be automated without needing a full redesign for every installation. For example, most modern apartments will have space heating, water heating and ventilation systems but some have windows that can be opened while others do not. Automated window-opening gives the system a way to improve air quality with a lower energy requirement than mechanical ventilation and can also be used for passive cooling.

The same flexibility allows onsite energy generation systems, such as photovoltaic panels or solar thermal cells, to be used to supplement mains electricity.

Integration of all aspects of the building services under a single control system avoids conflict between different services. To extend the example of the automated windows, automation would switch off any space heating or air-conditioning as soon as the windows are opened. Even where the windows are not automated, they may be fitted with sensors so that opening them manually would have the same effect.

The current generation of building operating systems can be controlled using a phone or tablet but still depend on the home’s occupants setting the parameters for its operation. The next generation will use machine learning so that every system learns the behaviour of the building into which it is installed, to further improve its energy efficiency.

All-electric is our preferred service option for an apartment that is sufficiently insulated so it does not need wet central heating

The Atamate view

All-electric is our preferred service option for an apartment that is sufficiently insulated so it does not need wet central heating.

We acknowledge that we are not disinterested; our core product is the sort of operating system needed to make all-electric heating a viable option. However, our product can operate in any building service layout so we are not committed to the service layout described here.

Our case studies have shown our system delivers improvements to comfort, convenience and energy efficiency to a wide variety of buildings with different energy sources and service types. Rather, our preference is underpinned by the fast response of all-electric space-heating units, which makes the best use of the occupancy-based zonal control system while avoiding overheating.

Unfortunately, both all-electric heating and automation have been largely overlooked in much of the conversation about decarbonising the domestic sector.

Options requiring higher levels of investment, such as hydrogen power, district heating and air-source heat pumps, have been given much more attention by advisory bodies like the Climate Change Committee (CCC) and in government policy documents like the Future Homes consultation.

Our post-occupancy evaluation studies have shown that the combination of automation and all-electric power compares extremely well with other options, delivering a level of energy efficiency that meets even the stringent standards required by the Passivhaus Trust and is compatible with the infrastructure already in place.

However, we do not assume that the all-electric option will be optimal for every apartment block. Our position is simply that it should be among the range of options that should be compared at any project’s design stage and that the comparison should be based on a range of metrics including cost, comfort and carbon.